I, rather notoriously (talk to some of the people at Central Dallas Ministries), don’t do management. I may do a little administration, when I have to, but that’s about as far as I’m willing to go.

Not doing management is mostly a matter of choice for me. I think I could probably do it if I wanted to, but I want to do things myself; not tell other people what to do. We do have processes for the things we need to have them for—mostly accounting and financial (my good friend and brilliant CPA, Tom Millner, was the first new person we brought on board when we started Central Dallas CDC, and he doesn’t mind doing a little management). We don’t have any rules or regulations that we don’t need to handle money safely or to satisfy the requirements of the law or grants we’re working under.

I understand that refusing to be a manager is limiting in some ways. I can run an organization of five or six (that’s roughly how big we are) without being a manager because I know everybody who works here pretty well. I know what they do and have a pretty good idea of their strengths and weaknesses. I know where I may be able to help them and where I won’t.

It also works because the people working at Central Dallas CDC have lots of strengths, not many weaknesses, and are extremely dedicated. I imagine (because I don’t really know) that the atmosphere working here is similar to places like the early days of Google or some other Silicon Valley start up. Everything may look chaotic, but you feel the energy in air. It almost makes your hair stand on end. I don’t need to look over people’s shoulders to make sure they work. I can’t even imagine working in an environment where that was necessary, and I would probably just go do something else if it ever did.

Our organizational chart is almost flat. Theoretically people report to me, but everyone has their own area of expertise and they know more about it then I do. We don’t have any mediocre people here.

Whether my dread of becoming a manager will ever prove a problem for Central Dallas CDC is hard to say. Most real estate development companies, even for-profits, are small. The business is for entrepreneurs; for people who aren’t afraid of risks. To do it you have to love the art of the deal and thrive on challenges. It is hard to systematize, although a few large companies have found a way to do that successfully. Thankfully, by the time we get big enough to need a manager rather than an entrepreneur in charge, it will probably be my successor’s problem.

In any event, if you ever decide you want to work here, or volunteer a few hours, don’t ask what our process is or our requirements are for volunteers. We don’t have them. Send me your resume and I’ll put it in my file in case I’m ever asked to write a recommendation, but I won’t do more than glance at it before I talk to you.

I want to know who you are and what you can do. Show me your energy and your ideas and your skills and your passion for our work and you’ll be somebody I want to work with and we’ll find a way to make it happen. My idea of the perfect co-worker would be someone I hire the day before I go on a two-week vacation (if I ever get around to taking such a vacation) and when I get back then I find out he or she has put together a deal to house fifty people that are now homeless, found the site, figured out how to finance it, and it only waiting for me to come back to sign the formal documents.

That’s the day I get to retire.

Saturday, May 30, 2009

Wednesday, May 27, 2009

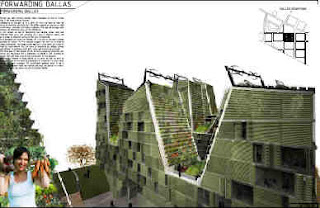

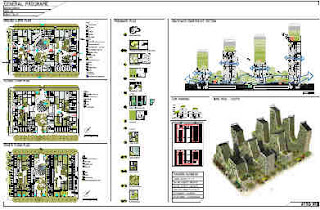

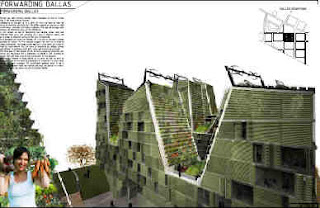

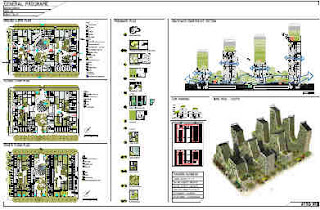

Vision Dallas: The Winning Designs!

The winning designs for Re:Vision Dallas have been announced. You can take a quick look at them here:

But we’ve copied at least one view from each design. A lot more information will be available soon on the Urban Re:Vision website and I’ll be discussing all of them in detail in my blog, but I hope that you’ll start looking and thinking, and I look forward to hearing from you about what you like and don’t like in each of the designs.

Tuesday, May 26, 2009

Vision Dallas: More Jury Deliberations

The second day of jury deliberations for the Re:Vision Dallas competition to design a sustainable city block began with enormous optimism. After looking at the results from the first day, it was obvious that the jury had retained most of the entries from the first couple hours of deliberations but the longer day went the fewer entries made it to the second round.

The assumption was that as the jury became more accustomed to the quality of the entries that the jury became tougher. Everyone thought that a quick review of the entries from yesterday, applying the tougher standard set by the entries themselves, would result in narrowing the remaining entries pretty quickly.

Unfortunately, everyone was wrong. Whether by happenstance or otherwise (the entries were numbered by their registration date, so maybe the earlier registrants had spent more time on their designs) the earlier entries were, as a group, simply better.

Several hours of work only resulted in reducing the remaining designs from about thirty to twenty-one. Worse yet, occasionally a judge would reach back into the entries that had already been eliminated and find reason to bring it back, so progress was slow and sometimes no progress at all was made.

Finally the jury decided to try a different tack. The twenty or so remaining entries were laid out on long tables, and the jury starting looking for exceptional entries; for the winners rather than for entries that could be eliminated.

Two entries immediately came to the forefront as exceptional in design, in innovation and in the quality of their thought. Another four or five entries had something more to recommend them than the competition (at least in the jury’s eyes). Now the task became picking the best entry from those few entries to join the two winners already selected.

Once again the deliberations slowed down as the jury discussed the relative merits of the various designs, but after some time the candidates for the third winning entry were narrowed to two, and then the jury decided to vote between them. As each juror stated his opinion, though, a consensus emerged, and in the end there was no need to vote. The winning entries had been selected.

And I was enormously relieved. The winning designs were beautiful and they all looked buildable. I didn’t realize how worried I had been that the jury might select winners that I couldn’t build until the decision was made.

The assumption was that as the jury became more accustomed to the quality of the entries that the jury became tougher. Everyone thought that a quick review of the entries from yesterday, applying the tougher standard set by the entries themselves, would result in narrowing the remaining entries pretty quickly.

Unfortunately, everyone was wrong. Whether by happenstance or otherwise (the entries were numbered by their registration date, so maybe the earlier registrants had spent more time on their designs) the earlier entries were, as a group, simply better.

Several hours of work only resulted in reducing the remaining designs from about thirty to twenty-one. Worse yet, occasionally a judge would reach back into the entries that had already been eliminated and find reason to bring it back, so progress was slow and sometimes no progress at all was made.

Finally the jury decided to try a different tack. The twenty or so remaining entries were laid out on long tables, and the jury starting looking for exceptional entries; for the winners rather than for entries that could be eliminated.

Two entries immediately came to the forefront as exceptional in design, in innovation and in the quality of their thought. Another four or five entries had something more to recommend them than the competition (at least in the jury’s eyes). Now the task became picking the best entry from those few entries to join the two winners already selected.

Once again the deliberations slowed down as the jury discussed the relative merits of the various designs, but after some time the candidates for the third winning entry were narrowed to two, and then the jury decided to vote between them. As each juror stated his opinion, though, a consensus emerged, and in the end there was no need to vote. The winning entries had been selected.

And I was enormously relieved. The winning designs were beautiful and they all looked buildable. I didn’t realize how worried I had been that the jury might select winners that I couldn’t build until the decision was made.

Monday, May 25, 2009

Vision Dallas: A Brief Note on the Jury’s First Day

The first day of the jury is over, and I thought I’d post a brief note. The day was both exhausting and exhilarating. There were 90 qualified entrants for the project (just a few were disqualified for gross violations of the rules—the folks at Re:Vision were generous in letting entries go to the jury). There was also one last minute substitution on the jury—Cameron from Architecture for Humanity was called away on a project, so Nathaniel Corum, author of Building a Straw Bale House, filled in admirably for him.

Nathaniel is an interesting man (he’s in the center with his back to the camera of the two jury photos here). He’s spent much of the last several years working to improve housing on Indian Reservations in South Dakota, Montana, Arizona and New Mexico—mostly straw bale houses. The newest technique he is pioneering is tilt-wall straw bale houses—he could explain (especially with drawings), I can’t in a short essay. But it’s radical, innovative work.

The pictures of the jury don’t show very much, but the day was grueling. Trying to review ninety entries is an overwhelming task. Many of the entries had not only the six pictorial boards called for by the competition rules, but also as many as twenty or thirty pages of supporting material. There were charts, graphs, spreadsheets and other types of graphical representations as well. Even working ten hours, that meant reviewing a new submission every five to seven minutes.

The jury worked by projecting the projects on a large wall screen so that every one could see them. A number of projects were quickly eliminated, usually for one of two reasons. If a project wasn’t well designed (I would have said if it were ugly), then it wouldn’t advance. If a project wasn’t buildable, then it also wouldn’t advance. Sometimes that was immediately obvious. Sometimes only by reviewing the supporting material was it possible to know if the designer had done sufficient work to indicate that something that might have looked improbable could be built.

Of course there were a few outliers. Projects that were well beyond budget or that did something other than what we had asked for in the contest rules—but, as allowed, made an argument that even though it wasn’t what we had envisioned, it was a better approach.

Finally we had the entrants whittled down to about thirty, our goal for the day. A few of the more unusual ideas that entrants proposed were sent with someone as homework so that the most expert juror in that area could try to assess whether the idea proposed really worked. Then the jury adjourned and went to dinner.

Nathaniel is an interesting man (he’s in the center with his back to the camera of the two jury photos here). He’s spent much of the last several years working to improve housing on Indian Reservations in South Dakota, Montana, Arizona and New Mexico—mostly straw bale houses. The newest technique he is pioneering is tilt-wall straw bale houses—he could explain (especially with drawings), I can’t in a short essay. But it’s radical, innovative work.

The pictures of the jury don’t show very much, but the day was grueling. Trying to review ninety entries is an overwhelming task. Many of the entries had not only the six pictorial boards called for by the competition rules, but also as many as twenty or thirty pages of supporting material. There were charts, graphs, spreadsheets and other types of graphical representations as well. Even working ten hours, that meant reviewing a new submission every five to seven minutes.

The jury worked by projecting the projects on a large wall screen so that every one could see them. A number of projects were quickly eliminated, usually for one of two reasons. If a project wasn’t well designed (I would have said if it were ugly), then it wouldn’t advance. If a project wasn’t buildable, then it also wouldn’t advance. Sometimes that was immediately obvious. Sometimes only by reviewing the supporting material was it possible to know if the designer had done sufficient work to indicate that something that might have looked improbable could be built.

Of course there were a few outliers. Projects that were well beyond budget or that did something other than what we had asked for in the contest rules—but, as allowed, made an argument that even though it wasn’t what we had envisioned, it was a better approach.

Finally we had the entrants whittled down to about thirty, our goal for the day. A few of the more unusual ideas that entrants proposed were sent with someone as homework so that the most expert juror in that area could try to assess whether the idea proposed really worked. Then the jury adjourned and went to dinner.

Sunday, May 24, 2009

Crop Circles

Flying to San Francisco my eye was drawn to crop circles. I don’t mean the kind of crop circles that were supposedly created by aliens and made such a stir a few years ago in England, I mean the kind created by pivot irrigation as in the photograph here. When I first came to the southwest from Michigan, (where water is never in short supply), I had no idea what I was seeing. Nothing in nature makes a perfect circle, and I did not understand why any farmer would irrigate in a fashion that left some of his land too dry to cultivate.

In the Midwest where water is plentiful and the land rich, farmers more and more cultivate every square inch that they own. It is a perpetual effort to persuade landowners to leave some small portion of land uncultivated so animals and game and song birds have a place live.

After a little time I finally understood why farmers acted differently here in the southwest. It is water that is valuable, not land. Land is relatively cheap. The problem is that there is not enough water to irrigate it all, or even any large portion of it.

In much of west Texas and north along the high plains, the primary source of water for irrigation is the Ogallala Aquifer. The origin of the Ogallala Aquifer dates back between two and six million years ago. Since the Ogallala started to be used for irrigation in the 1950s, its water level has dropped almost 9%. More efficient means of water use—including pivot irrigation—have slowed the decline in recent years. As you can see from the map of the Ogallala, some regions of the aquifer have actually begun to see rises in its level, while others have continued to decline.

is the Ogallala Aquifer. The origin of the Ogallala Aquifer dates back between two and six million years ago. Since the Ogallala started to be used for irrigation in the 1950s, its water level has dropped almost 9%. More efficient means of water use—including pivot irrigation—have slowed the decline in recent years. As you can see from the map of the Ogallala, some regions of the aquifer have actually begun to see rises in its level, while others have continued to decline.

At least in Texas it’s clear that we have to do even more work on water conservation or some day the level of the Ogallala will drop so far that irrigation will become impractical, and I won’t see any more crop circles flying to San Francisco. If that should come, and global warming threatens to bring that day about more quickly, it will mean that thousands of acres of now productive land will have been lost, and a way of life on Texas ranches and farms will come closer to disappearing.

In the Midwest where water is plentiful and the land rich, farmers more and more cultivate every square inch that they own. It is a perpetual effort to persuade landowners to leave some small portion of land uncultivated so animals and game and song birds have a place live.

After a little time I finally understood why farmers acted differently here in the southwest. It is water that is valuable, not land. Land is relatively cheap. The problem is that there is not enough water to irrigate it all, or even any large portion of it.

In much of west Texas and north along the high plains, the primary source of water for irrigation

is the Ogallala Aquifer. The origin of the Ogallala Aquifer dates back between two and six million years ago. Since the Ogallala started to be used for irrigation in the 1950s, its water level has dropped almost 9%. More efficient means of water use—including pivot irrigation—have slowed the decline in recent years. As you can see from the map of the Ogallala, some regions of the aquifer have actually begun to see rises in its level, while others have continued to decline.

is the Ogallala Aquifer. The origin of the Ogallala Aquifer dates back between two and six million years ago. Since the Ogallala started to be used for irrigation in the 1950s, its water level has dropped almost 9%. More efficient means of water use—including pivot irrigation—have slowed the decline in recent years. As you can see from the map of the Ogallala, some regions of the aquifer have actually begun to see rises in its level, while others have continued to decline.At least in Texas it’s clear that we have to do even more work on water conservation or some day the level of the Ogallala will drop so far that irrigation will become impractical, and I won’t see any more crop circles flying to San Francisco. If that should come, and global warming threatens to bring that day about more quickly, it will mean that thousands of acres of now productive land will have been lost, and a way of life on Texas ranches and farms will come closer to disappearing.

Saturday, May 23, 2009

Sour Milk

We’ve had some milk go sour at home this week. Something I’m sure almost all of you have had happen to you. Of course I won’t throw it away. I’ll find a way to use it. I don’t believe in wasting anything that you can use. But it’s started me thinking about a bit of food history.

There are dozens of old recipes that call for sour milk. Part of the reason is that before refrigeration, when the cows were producing a lot of milk, then you had to find a way to use it up. Cheese (“milk’s leap to immortality”) was one result. Milk didn’t keep very long before going sour.

But using sour milk wasn’t only a way of using up food resources that you couldn’t afford to lose. It was actually necessary to make certain kinds of breads. Back in the good old days, before sliced bread and preservatives, if you wanted bread then you had to make it. Everyone wanted bread, it was one of the basics of life, and it had the advantage that, in the form of flour, it could be stored indefinitely (or until the weevils got into it). Making yeast bread, though, is a big effort and somewhat unpredictable. You have to proof the yeast, mix and knead the dough, let it rise, punch it down, and then let it rise again before you can bake it. Even if everything goes well, the process takes a couple of hours and you can’t wander away while it’s going on, although you can do other work and check back from time to time. The results depend on the temperature, the humidity, the amount of moisture in your flour and dozens of other unpredictable factors.

Contrary to family histories, most of your great-great-grandmothers probably couldn’t make very good yeast bread consistently. Ingredients weren’t uniform and trying to get an even heat in a wood stove for baking is extremely difficult.

Even the hardest working cook (almost always women in the early days of this country) would find it difficult to make yeast bread every day. This is especially true when you think about how difficult it was to do all the other every day tasks by hand—laundry, making butter, making soap, etc. There just wasn’t time. In Europe and the larger and older cities in the United States you could buy your bread from the baker. Many of the traditionally homemade bread that we have were only made once per week—on the baker’s day off. But on the frontier and in the small towns of America, there wasn’t a baker, so you were on your own.

The salvation of many cooks was “quick bread”. That’s bread that is leavened by use of a “mechanical” leaven rather than yeast. The earliest quick breads were leavened with ashes. But wood ash (at least the one time I tried it) leads to a heavy, dense loaf

that tends to taste gritty. Baking soda was an enormous step forward. It’s pure sodium bicarbonate and when combined with moisture and an acid, baking soda releases carbon dioxide and causes rising.

If you try to make soda bread with regular milk, it won’t rise. The milk is not acidic enough. But if you use sour milk, than the baking soda will react with the acid in it and you can make a nice chewy loaf that rises. Of course there are other sources of the acid you need to combine with baking soda to make bread, but for our forefathers sour milk was no reason for worry. Sour milk meant soda bread (yes, I’m Irish by descent) and that was a good thing.

The next time you have milk go sour don’t throw it away. Think of your ancestors and the nutrition they got from bread made from sour milk. Nutrition important enough so that if they had thrown out sour milk; they may not have survived and you might not be here today. Instead, in their honor, make yourself a loaf of soda bread. Here’s a recipe:

Irish Soda Bread

3 cups white flour

2 cups whole wheat flour

2 teaspoons baking soda

1 tablespoon baking powder

2 tablespoons brown sugar

2 ¼ cups sour milk (you can also use buttermilk)

Mix all the dry ingredients together, then add the sour milk all at once. Stir the ingredients with a wooden spoon until just mixed. Turn out and knead for a brief moment. Divide the dough into two round loafs, place each on a baking sheet and let rise for ten minutes. Slash a cross in the top of each loaf in honor of St. Patrick and bake in a 400 degree oven for about forty minutes. It’s best eaten within a day, and even better eaten with sweet butter while it’s still warm.

P.S. Not all milk that has gone bad is sour milk. Make sure you know the difference between “soured” and “spoiled”.

There are dozens of old recipes that call for sour milk. Part of the reason is that before refrigeration, when the cows were producing a lot of milk, then you had to find a way to use it up. Cheese (“milk’s leap to immortality”) was one result. Milk didn’t keep very long before going sour.

But using sour milk wasn’t only a way of using up food resources that you couldn’t afford to lose. It was actually necessary to make certain kinds of breads. Back in the good old days, before sliced bread and preservatives, if you wanted bread then you had to make it. Everyone wanted bread, it was one of the basics of life, and it had the advantage that, in the form of flour, it could be stored indefinitely (or until the weevils got into it). Making yeast bread, though, is a big effort and somewhat unpredictable. You have to proof the yeast, mix and knead the dough, let it rise, punch it down, and then let it rise again before you can bake it. Even if everything goes well, the process takes a couple of hours and you can’t wander away while it’s going on, although you can do other work and check back from time to time. The results depend on the temperature, the humidity, the amount of moisture in your flour and dozens of other unpredictable factors.

Contrary to family histories, most of your great-great-grandmothers probably couldn’t make very good yeast bread consistently. Ingredients weren’t uniform and trying to get an even heat in a wood stove for baking is extremely difficult.

Even the hardest working cook (almost always women in the early days of this country) would find it difficult to make yeast bread every day. This is especially true when you think about how difficult it was to do all the other every day tasks by hand—laundry, making butter, making soap, etc. There just wasn’t time. In Europe and the larger and older cities in the United States you could buy your bread from the baker. Many of the traditionally homemade bread that we have were only made once per week—on the baker’s day off. But on the frontier and in the small towns of America, there wasn’t a baker, so you were on your own.

The salvation of many cooks was “quick bread”. That’s bread that is leavened by use of a “mechanical” leaven rather than yeast. The earliest quick breads were leavened with ashes. But wood ash (at least the one time I tried it) leads to a heavy, dense loaf

that tends to taste gritty. Baking soda was an enormous step forward. It’s pure sodium bicarbonate and when combined with moisture and an acid, baking soda releases carbon dioxide and causes rising.

If you try to make soda bread with regular milk, it won’t rise. The milk is not acidic enough. But if you use sour milk, than the baking soda will react with the acid in it and you can make a nice chewy loaf that rises. Of course there are other sources of the acid you need to combine with baking soda to make bread, but for our forefathers sour milk was no reason for worry. Sour milk meant soda bread (yes, I’m Irish by descent) and that was a good thing.

The next time you have milk go sour don’t throw it away. Think of your ancestors and the nutrition they got from bread made from sour milk. Nutrition important enough so that if they had thrown out sour milk; they may not have survived and you might not be here today. Instead, in their honor, make yourself a loaf of soda bread. Here’s a recipe:

Irish Soda Bread

3 cups white flour

2 cups whole wheat flour

2 teaspoons baking soda

1 tablespoon baking powder

2 tablespoons brown sugar

2 ¼ cups sour milk (you can also use buttermilk)

Mix all the dry ingredients together, then add the sour milk all at once. Stir the ingredients with a wooden spoon until just mixed. Turn out and knead for a brief moment. Divide the dough into two round loafs, place each on a baking sheet and let rise for ten minutes. Slash a cross in the top of each loaf in honor of St. Patrick and bake in a 400 degree oven for about forty minutes. It’s best eaten within a day, and even better eaten with sweet butter while it’s still warm.

P.S. Not all milk that has gone bad is sour milk. Make sure you know the difference between “soured” and “spoiled”.

Friday, May 22, 2009

What do you see?, Part II

I know that I see the world in a limited way. The standard greeting in Nepal, and apparently some other places in South Asia is “Namaste”. The word means something roughly like “I honor the light of God within you”. I imagine that in everyday life the word has become simply a rote phrase with little thought for its meaning. Much in the same way, we say “Good-bye” usually without thinking of its original meaning “God be with ye”.

I’ve never been to Nepal. The closest I’ve come is a couple years exchange of letters with a friend who served in the Peace Corp there. But on occasion, I’ve met people who don’t look at someone and see their outward appearance, but look within and honor the image of God that is within us all, no matter how disheveled and dirty someone may be.

People that see that way are in my mind Saints. Not in any theological sense—I am probably the world’s worst theologian. But in the sense that people that see the image of God in every person they meet model the goodness to which I aspire.

In the unlikely event that I ever reach that goal, then I will set myself the new goal of seeing the world as the poet and engraver William Blake saw it:

“When the Sun rises, do you not See a round Disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea?’ O no no I see an Innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying ‘Holy Holy Holy is the Lord God Almighty!’”

Unfortunately Blake did not leave us an engraving to match these words, but the engraving copied here, The Great Red Dragon and the Women Clothed with Sun, gives you some idea how Blake may have seen the rising sun.

Unfortunately Blake did not leave us an engraving to match these words, but the engraving copied here, The Great Red Dragon and the Women Clothed with Sun, gives you some idea how Blake may have seen the rising sun.

Until that day comes, I will begin by trying to remember that a greeting can mean more than “Hello” and that good-bye can mean more than “I’m leaving now.”

I’ve never been to Nepal. The closest I’ve come is a couple years exchange of letters with a friend who served in the Peace Corp there. But on occasion, I’ve met people who don’t look at someone and see their outward appearance, but look within and honor the image of God that is within us all, no matter how disheveled and dirty someone may be.

People that see that way are in my mind Saints. Not in any theological sense—I am probably the world’s worst theologian. But in the sense that people that see the image of God in every person they meet model the goodness to which I aspire.

In the unlikely event that I ever reach that goal, then I will set myself the new goal of seeing the world as the poet and engraver William Blake saw it:

“When the Sun rises, do you not See a round Disk of fire somewhat like a Guinea?’ O no no I see an Innumerable company of the Heavenly host crying ‘Holy Holy Holy is the Lord God Almighty!’”

Unfortunately Blake did not leave us an engraving to match these words, but the engraving copied here, The Great Red Dragon and the Women Clothed with Sun, gives you some idea how Blake may have seen the rising sun.

Unfortunately Blake did not leave us an engraving to match these words, but the engraving copied here, The Great Red Dragon and the Women Clothed with Sun, gives you some idea how Blake may have seen the rising sun.Until that day comes, I will begin by trying to remember that a greeting can mean more than “Hello” and that good-bye can mean more than “I’m leaving now.”

Thursday, May 21, 2009

What do you see?, Part I

There are times when I am reminded that you and I don’t see the world the same way. My wife comes from South Texas. You can see in the picture what it looks like—on a good day. I come from Glen Lake, Michigan, and I’ve put a picture up of Glen Lake as well, so you can see what it looks like.

For the life of me I cannot understand what my wife sees in South Texas, but it’s beautiful to her eyes. It is just as beautiful to her as Glen Lake is to me. (Objective observers would, of course, find Glen Lake far more beautiful!).

Everything we do, remember and have been influences how we see the world. Once I was examined by two lawyers selecting a jury. The prosecutor asked me: “Do you think your experience as an attorney would influence how you reach your decision in this case?”

I answered “Yes”.

The defense attorney asked if I could put those experiences aside and make a fair judgment solely on the facts as presented and the Court’s instructions.

Once again I answered “Yes”.

The two attorneys repeated the same questions twice more, always getting the same answer from me. Finally the judge became exasperated with me, and asked which was it, would the fact that I was attorney affect how I came to a judgment, or could I put that aside and be fair.

I answered: “Both your honor, my experience as an attorney affects how I see the world but I think I can make a judgment based on the facts and your instructions.” At that point the judge threw me out of the courtroom. As mad as he was, I was lucky not to be held in contempt.

I still think my answers to both questions were true. I would have made the same answer to the first question if I had been asked if that fact that I was white or Irish or loved basketball or had two children or had a cup of coffee for breakfast would affect my judgment.

If, however, I had been asked if South Texas were beautiful, then that would be a question where I could answer “No”.

For the life of me I cannot understand what my wife sees in South Texas, but it’s beautiful to her eyes. It is just as beautiful to her as Glen Lake is to me. (Objective observers would, of course, find Glen Lake far more beautiful!).

Everything we do, remember and have been influences how we see the world. Once I was examined by two lawyers selecting a jury. The prosecutor asked me: “Do you think your experience as an attorney would influence how you reach your decision in this case?”

I answered “Yes”.

The defense attorney asked if I could put those experiences aside and make a fair judgment solely on the facts as presented and the Court’s instructions.

Once again I answered “Yes”.

The two attorneys repeated the same questions twice more, always getting the same answer from me. Finally the judge became exasperated with me, and asked which was it, would the fact that I was attorney affect how I came to a judgment, or could I put that aside and be fair.

I answered: “Both your honor, my experience as an attorney affects how I see the world but I think I can make a judgment based on the facts and your instructions.” At that point the judge threw me out of the courtroom. As mad as he was, I was lucky not to be held in contempt.

I still think my answers to both questions were true. I would have made the same answer to the first question if I had been asked if that fact that I was white or Irish or loved basketball or had two children or had a cup of coffee for breakfast would affect my judgment.

If, however, I had been asked if South Texas were beautiful, then that would be a question where I could answer “No”.

Wednesday, May 20, 2009

Banking Should Not Be Exciting

My good friend and former law partner, Ken Koonce, sent me the following quotation:

“"Banking should not be exciting. If banking is exciting there is something wrong with it." CLAY EWING, president of German American Bancorp., a community bank in Jasper, Ind.” [The entire article is worth reading, so click on the link].

For years Ken and I have argued good-naturedly about anything and everything—it’s sort of a lawyer’s recreation—but on this point we agree: Banking should not be exciting.

There are certain activities, and banking is paramount among them, that require caution. As the saying goes, there are bold pilots, and there are old pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots. There aren’t old, bold banks either.

For years community banks, savings and loan associations and credit unions have run on the 3-6-3 rule: Pay 3% interest on deposits, charge 6% interest on loans and be on the golf course by 3:00 p.m. Many still operate on this system and, on the whole, that’s a good thing. The bank makes a modest amount of money and your deposits are safe.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t want a brilliant, energetic, innovative technocrat handling the money in my savings account. If I wanted that, then I’d put the money in some high tech start up. For my banker, a dull and stolid person who regards doing yard work as excitement enough, is just the right person. Let banker’s work short hours for modest pay. Let them have no new ideas and take no risks. Everything has its place and banks are places of quiet and order—no place for the ambitious.

We are not all the same and thank God for our differences. Not everyone needs to be brilliant. Not everyone needs to be rich. Not everyone needs to work eighty hours per week. Some jobs and some businesses are best served by a person that clocks out after eight hours and goes home—where his or her family and real life are.

or her family and real life are.

The next time I am in the market for a new banker, I think I’ll head to the golf course at 3:00 p.m. and find one on the links. Then at least I’ll know he’s not in the office thinking up some new and more exciting way to lose my money. Unfortunately, the banker in the picture has retired from banking to full-time golf.

“"Banking should not be exciting. If banking is exciting there is something wrong with it." CLAY EWING, president of German American Bancorp., a community bank in Jasper, Ind.” [The entire article is worth reading, so click on the link].

For years Ken and I have argued good-naturedly about anything and everything—it’s sort of a lawyer’s recreation—but on this point we agree: Banking should not be exciting.

There are certain activities, and banking is paramount among them, that require caution. As the saying goes, there are bold pilots, and there are old pilots, but there are no old, bold pilots. There aren’t old, bold banks either.

For years community banks, savings and loan associations and credit unions have run on the 3-6-3 rule: Pay 3% interest on deposits, charge 6% interest on loans and be on the golf course by 3:00 p.m. Many still operate on this system and, on the whole, that’s a good thing. The bank makes a modest amount of money and your deposits are safe.

I don’t know about you, but I don’t want a brilliant, energetic, innovative technocrat handling the money in my savings account. If I wanted that, then I’d put the money in some high tech start up. For my banker, a dull and stolid person who regards doing yard work as excitement enough, is just the right person. Let banker’s work short hours for modest pay. Let them have no new ideas and take no risks. Everything has its place and banks are places of quiet and order—no place for the ambitious.

We are not all the same and thank God for our differences. Not everyone needs to be brilliant. Not everyone needs to be rich. Not everyone needs to work eighty hours per week. Some jobs and some businesses are best served by a person that clocks out after eight hours and goes home—where his

or her family and real life are.

or her family and real life are.The next time I am in the market for a new banker, I think I’ll head to the golf course at 3:00 p.m. and find one on the links. Then at least I’ll know he’s not in the office thinking up some new and more exciting way to lose my money. Unfortunately, the banker in the picture has retired from banking to full-time golf.

Tuesday, May 19, 2009

A Man and a Turtle

(John is in San Francisco taking part in the ReVision Dallas design competition. Look for his posts on the results and his thoughts upon his return. This piece and others that may appear on his blog were written prior to his leaving. Enjoy!)

Driving home yesterday afternoon, I saw a car stopped in the right lane, emergency blinkers on. I slowed down and pulled to the left. When I passed I looked out the window to see what the problem might be.

A man, dressed for the office, was marching solemnly down the embankment through the muddy grass towards the Jackson Branch. His elbows were held out to the side and in his hands, held well away from his body, was an enormous turtle—at least the size of a dinner platter.

An entire story sprang to mind. The man is driving home from work when he sees an enormous turtle in his lane. He slows, then stops and puts the blinkers on so he won’t be rear ended. Now he has a decision to make. He looks at the turtle, then at the muddy bank, then ruefully at his shoes.

Decision made he unbuckles his seatbelt and walks around to the front of his car. Again he looks at the turtle. Then he carefully picks the turtle up wondering whether turtles bite and watchful of his clothes.

Watching him there was enormous ceremony to his steps. This well-dressed man had decided that a turtle was worth both his time and muddy shoes.

Driving home yesterday afternoon, I saw a car stopped in the right lane, emergency blinkers on. I slowed down and pulled to the left. When I passed I looked out the window to see what the problem might be.

A man, dressed for the office, was marching solemnly down the embankment through the muddy grass towards the Jackson Branch. His elbows were held out to the side and in his hands, held well away from his body, was an enormous turtle—at least the size of a dinner platter.

An entire story sprang to mind. The man is driving home from work when he sees an enormous turtle in his lane. He slows, then stops and puts the blinkers on so he won’t be rear ended. Now he has a decision to make. He looks at the turtle, then at the muddy bank, then ruefully at his shoes.

Decision made he unbuckles his seatbelt and walks around to the front of his car. Again he looks at the turtle. Then he carefully picks the turtle up wondering whether turtles bite and watchful of his clothes.

Watching him there was enormous ceremony to his steps. This well-dressed man had decided that a turtle was worth both his time and muddy shoes.

Monday, May 18, 2009

Vision Dallas: Off to San Francisco

The Re:Vision Dallas design competition has closed. Ninety-five entries were received and I’m leaving Sunday to be in San Francisco Monday and Tuesday to observe the competition jury at work. I am excited beyond words. I will get to spend two days seeing the work of brilliant architects and designers critiqued by five brilliant and learned judges. I expect to learn more about sustainable design in those two days than I could in years of studying on my own.

The judges for the competition are so distinguished and accomplished that I can only briefly summarize who they are:

Aidan Hughes leads the North American planning practice for Arup, a global firm that has done buildings, consulting and infrastructure in at least 68 countries, on every continent but Antarctica. Just a glance through its portfolio will show you everything from shopping malls in Borneo, to pedestrian bridges in Italy, to a subway station in New York. You can see a selection of their projects here: http://www.arup.com/arup/projects.cfm.

Aidan Hughes leads the North American planning practice for Arup, a global firm that has done buildings, consulting and infrastructure in at least 68 countries, on every continent but Antarctica. Just a glance through its portfolio will show you everything from shopping malls in Borneo, to pedestrian bridges in Italy, to a subway station in New York. You can see a selection of their projects here: http://www.arup.com/arup/projects.cfm.

Cameron Sinclair is the Executive Director of Architecture for Humanity and co-author of Design Like You Give A Damn. Among other honors, his efforts to find architectural solutions to humanitarian needs has led the World Economic Forum to name him as a Young Global Leader. You can see more about the work of Architecture for Humanity here: http://www.architectureforhumanity.org/.

Cameron Sinclair is the Executive Director of Architecture for Humanity and co-author of Design Like You Give A Damn. Among other honors, his efforts to find architectural solutions to humanitarian needs has led the World Economic Forum to name him as a Young Global Leader. You can see more about the work of Architecture for Humanity here: http://www.architectureforhumanity.org/.

Eric Corey Freed is a principal at organicARCHITECT and the author of Green Building and Architecture for Dummies. organicARCHITECT is considered a leader in the field; named by San Francisco Magazine "Best Green Architect" in 2005 and "Best Visionary" in 2007; and "Green Visionary" by 7x7 Magazine in 2008. You can see the online journal, Ecotecture, which Eric helped found here: http://www.ecotecture.com/.

Eric Corey Freed is a principal at organicARCHITECT and the author of Green Building and Architecture for Dummies. organicARCHITECT is considered a leader in the field; named by San Francisco Magazine "Best Green Architect" in 2005 and "Best Visionary" in 2007; and "Green Visionary" by 7x7 Magazine in 2008. You can see the online journal, Ecotecture, which Eric helped found here: http://www.ecotecture.com/.

The judges for the competition are so distinguished and accomplished that I can only briefly summarize who they are:

Aidan Hughes leads the North American planning practice for Arup, a global firm that has done buildings, consulting and infrastructure in at least 68 countries, on every continent but Antarctica. Just a glance through its portfolio will show you everything from shopping malls in Borneo, to pedestrian bridges in Italy, to a subway station in New York. You can see a selection of their projects here: http://www.arup.com/arup/projects.cfm.

Aidan Hughes leads the North American planning practice for Arup, a global firm that has done buildings, consulting and infrastructure in at least 68 countries, on every continent but Antarctica. Just a glance through its portfolio will show you everything from shopping malls in Borneo, to pedestrian bridges in Italy, to a subway station in New York. You can see a selection of their projects here: http://www.arup.com/arup/projects.cfm. Cameron Sinclair is the Executive Director of Architecture for Humanity and co-author of Design Like You Give A Damn. Among other honors, his efforts to find architectural solutions to humanitarian needs has led the World Economic Forum to name him as a Young Global Leader. You can see more about the work of Architecture for Humanity here: http://www.architectureforhumanity.org/.

Cameron Sinclair is the Executive Director of Architecture for Humanity and co-author of Design Like You Give A Damn. Among other honors, his efforts to find architectural solutions to humanitarian needs has led the World Economic Forum to name him as a Young Global Leader. You can see more about the work of Architecture for Humanity here: http://www.architectureforhumanity.org/. Eric Corey Freed is a principal at organicARCHITECT and the author of Green Building and Architecture for Dummies. organicARCHITECT is considered a leader in the field; named by San Francisco Magazine "Best Green Architect" in 2005 and "Best Visionary" in 2007; and "Green Visionary" by 7x7 Magazine in 2008. You can see the online journal, Ecotecture, which Eric helped found here: http://www.ecotecture.com/.

Eric Corey Freed is a principal at organicARCHITECT and the author of Green Building and Architecture for Dummies. organicARCHITECT is considered a leader in the field; named by San Francisco Magazine "Best Green Architect" in 2005 and "Best Visionary" in 2007; and "Green Visionary" by 7x7 Magazine in 2008. You can see the online journal, Ecotecture, which Eric helped found here: http://www.ecotecture.com/.  Pliny Fisk is one of two Texans on the panel. He co-founded the Center for Maximum Potential Building Systems in 1975, and currently serves as Co-Director. The Center is recognized as the oldest architecture and planning 501C3 non-profit in the U.S. focused on sustainable design. In addition, Pliny also serves as a Fellow in Sustainable Urbanism and a Fellow in Health Systems Design at Texas A & M University where he holds a joint position as signature faculty in Architecture, Landscape Architecture and Planning. Professor Fisk’s researches on methods and materials for green building have been ground breaking.

Pliny Fisk is one of two Texans on the panel. He co-founded the Center for Maximum Potential Building Systems in 1975, and currently serves as Co-Director. The Center is recognized as the oldest architecture and planning 501C3 non-profit in the U.S. focused on sustainable design. In addition, Pliny also serves as a Fellow in Sustainable Urbanism and a Fellow in Health Systems Design at Texas A & M University where he holds a joint position as signature faculty in Architecture, Landscape Architecture and Planning. Professor Fisk’s researches on methods and materials for green building have been ground breaking.  Sergio Palleroni is the second Texan on the panel. He is a research fellow at the Center for Sustainable Development at the University of Texas. He has worked on housing and community development in the developing world since the 1970's, both for not-for-profit, governmental and international development and relief agencies such as the United Nations as well as the governments of Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Nicaragua, India and Tunisia. He has received numerous awards for his teaching and design work for underserved communities, including the National Design Award from the Smithsonian Institution and the White House Millenium Project in 2005. His books include: Time & Other Constructs: The Work of Carlos Miijares, co-authored with Rodolfo Santamaria; Studio at Large; Architecture in Service of Global Communities, with Christine Merkelbach; and Teaching Sustainability in Asia.

Sergio Palleroni is the second Texan on the panel. He is a research fellow at the Center for Sustainable Development at the University of Texas. He has worked on housing and community development in the developing world since the 1970's, both for not-for-profit, governmental and international development and relief agencies such as the United Nations as well as the governments of Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Nicaragua, India and Tunisia. He has received numerous awards for his teaching and design work for underserved communities, including the National Design Award from the Smithsonian Institution and the White House Millenium Project in 2005. His books include: Time & Other Constructs: The Work of Carlos Miijares, co-authored with Rodolfo Santamaria; Studio at Large; Architecture in Service of Global Communities, with Christine Merkelbach; and Teaching Sustainability in Asia. I look forward to watching the judging and trying to learn just a little bit about how the jury panel thinks; how the judges distinguish good design from better design; and how the panel comes to a decision about the winners and runners up.

I’ll try to keep the blog up to date so you can see my thoughts on the process.

Sunday, May 17, 2009

Eternity and Ham, Part III (fini)

In the year 711, Tariq b. Ziyad, the Muslim governor of Tangiers landed at Jabal Tariq (or Gibraltar as we would now say), the stone promontory named after him. He decisively beat the Visigoth Christian King Roderic, establishing a foothold for Islam in southern Spain. It took less than ten years for the Moors to conquer all of Spain except for a small portion of the country in the central and western Pyrenees.

In the year 711, Tariq b. Ziyad, the Muslim governor of Tangiers landed at Jabal Tariq (or Gibraltar as we would now say), the stone promontory named after him. He decisively beat the Visigoth Christian King Roderic, establishing a foothold for Islam in southern Spain. It took less than ten years for the Moors to conquer all of Spain except for a small portion of the country in the central and western Pyrenees.In about 720 Spanish resistance stiffened, and under the legendary leader Pelayo, the mountain Kingdom of Asturias in the northern Pyrenees defeated a Moorish army and sto pped their advance. That battle began the Reconquista, a war that continued, with many fits and stops, for more than 700 years until Boabdil, leader of Grenada, surrendered Alhambra, the last Moorish fortress in Spain, to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in 1492.

pped their advance. That battle began the Reconquista, a war that continued, with many fits and stops, for more than 700 years until Boabdil, leader of Grenada, surrendered Alhambra, the last Moorish fortress in Spain, to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in 1492.

pped their advance. That battle began the Reconquista, a war that continued, with many fits and stops, for more than 700 years until Boabdil, leader of Grenada, surrendered Alhambra, the last Moorish fortress in Spain, to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in 1492.

pped their advance. That battle began the Reconquista, a war that continued, with many fits and stops, for more than 700 years until Boabdil, leader of Grenada, surrendered Alhambra, the last Moorish fortress in Spain, to King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella in 1492. My mind cannot comprehend a war lasting for 700 years. Seven Hundred years ago Columbus had not yet been born, let alone sailed to America. Seven Hundred years is more than twenty generations. It’s time enough for your great-grandfather to have been born and die and all the generations through your great-grandchildren as well—and for that to happen half a dozen times. The impact on a people and culture must be enormous, almost incomprehensible.

In Spain, the signs of Moorish culture are everywhere. You see them in orange and almond groves; in white hilltop villages built as forts; and in the geometric and abstract designs of the south of Spain.

You also see signs of Moorish culture in the cuisine. Some of those signs are direct influences, such as spices like coriander and cumin or the use of almonds and oranges, but the Spanish love of ham, strangely enough, is also a result of the Moorish occupation of Spain.

After centuries of conflict, living together and intermarriage, it was difficult to remember who was a Muslim and who was a Christian. Especially because many people switched their religion depending on who was ruling the territory where they lived at any one time. A few cultural signs became key indicators.

One of the most important was whether you ate pork. If you ate pork, then you were a Christian. If you did not eat pork, then you were Muslim. After the Christian victory in 1492, given the looming terror of the Inquisition, it would have been a very bad idea to decide that even though you were a Christian, pork was just not to your taste.

Dishes that are made in Morocco with lamb, such as the small kebobs known as “pinchos”, are made with pork in Spain, even though the seasonings may be Middle Eastern.

As a result of the need to prove your identity as a Christian, Spain became a nation of lovers of pork, and of ham, and remains so to this day. Eating ham confirmed to the world that you were entitled to eternal salvation. So if you look closely, look at history and culture, you can see eternity, not only as a great ring of pure and endless light, but also as a bocadillo of jamon iberico. Or you can if you are Spanish, at least.

Saturday, May 16, 2009

Eternity and Ham, Part II

After writing yesterday’s essay I returned home and started rummaging in the refrigerator for dinner. Then I found it. A container of cold asparagus salad with ham vinaigrette (I told you I’d made every ham recipe you could imagine). The salad was still good, preserved by the oil and vinegar, so I finished the asparagus off for dinner, but I’m still worried that another ham dish may be lurking somewhere in the refrigerator—maybe behind the pickled green tomatoes or preserved lemons.

I am not entirely sure why eating an entire ham seems so difficult. I’m not usually bothered by eating the same food each day. Ham has an assertive flavor, though, and it’s not part of the normal palette of flavors in my diet. That’s not true everywhere. In Spain ham is a national obsession—asparagus with ham vinaigrette is a Spanish recipe.

There is a popular fast food restaurant called Museo de Jamon—literally, museum of ham. I visited one in Madrid and was entirely bewildered by the selection. As you can see, there are hundreds of hams and all of them are different both in price and, to the Spanish palate, taste. I quickly ordered a bocadillo (small sandwich)—the attendants are notoriously rude if you hesitate--with a random, moderately priced slice of ham. The sandwich was bread and ham and nothing else. The Spanish don’t believe in obscuring the taste of the ham with condiments.

There is a popular fast food restaurant called Museo de Jamon—literally, museum of ham. I visited one in Madrid and was entirely bewildered by the selection. As you can see, there are hundreds of hams and all of them are different both in price and, to the Spanish palate, taste. I quickly ordered a bocadillo (small sandwich)—the attendants are notoriously rude if you hesitate--with a random, moderately priced slice of ham. The sandwich was bread and ham and nothing else. The Spanish don’t believe in obscuring the taste of the ham with condiments.

Spanish ham is different from the ham we typically buy in the United States. Dryer, saltier, smokier, and aged, it is ham meant to last even without refrigeration. Such hams used to be common in the United States, but as James Beard writes in his classic American Cookery, “Nowadays one seldom finds a ham aged more than two or three years. Formerly it was not uncommon to find them aged six and seven years . . . .” While we have lost our taste for serious ham, the Spanish have not and debates about the best hams, generally acknowledged to be jamon iberico, and the best regions for ham, Huelva seems to be popular, are taken as seriously as debates here over the best wines.

best hams, generally acknowledged to be jamon iberico, and the best regions for ham, Huelva seems to be popular, are taken as seriously as debates here over the best wines.

The Spanish seem to eat ham almost every day, maybe more than once per day. Ham, for the Spanish, is important not only for cultural reasons, but as a tradition buttressed by religion, and that’s a topic to discuss tomorrow.

I am not entirely sure why eating an entire ham seems so difficult. I’m not usually bothered by eating the same food each day. Ham has an assertive flavor, though, and it’s not part of the normal palette of flavors in my diet. That’s not true everywhere. In Spain ham is a national obsession—asparagus with ham vinaigrette is a Spanish recipe.

There is a popular fast food restaurant called Museo de Jamon—literally, museum of ham. I visited one in Madrid and was entirely bewildered by the selection. As you can see, there are hundreds of hams and all of them are different both in price and, to the Spanish palate, taste. I quickly ordered a bocadillo (small sandwich)—the attendants are notoriously rude if you hesitate--with a random, moderately priced slice of ham. The sandwich was bread and ham and nothing else. The Spanish don’t believe in obscuring the taste of the ham with condiments.

There is a popular fast food restaurant called Museo de Jamon—literally, museum of ham. I visited one in Madrid and was entirely bewildered by the selection. As you can see, there are hundreds of hams and all of them are different both in price and, to the Spanish palate, taste. I quickly ordered a bocadillo (small sandwich)—the attendants are notoriously rude if you hesitate--with a random, moderately priced slice of ham. The sandwich was bread and ham and nothing else. The Spanish don’t believe in obscuring the taste of the ham with condiments.Spanish ham is different from the ham we typically buy in the United States. Dryer, saltier, smokier, and aged, it is ham meant to last even without refrigeration. Such hams used to be common in the United States, but as James Beard writes in his classic American Cookery, “Nowadays one seldom finds a ham aged more than two or three years. Formerly it was not uncommon to find them aged six and seven years . . . .” While we have lost our taste for serious ham, the Spanish have not and debates about the

best hams, generally acknowledged to be jamon iberico, and the best regions for ham, Huelva seems to be popular, are taken as seriously as debates here over the best wines.

best hams, generally acknowledged to be jamon iberico, and the best regions for ham, Huelva seems to be popular, are taken as seriously as debates here over the best wines.The Spanish seem to eat ham almost every day, maybe more than once per day. Ham, for the Spanish, is important not only for cultural reasons, but as a tradition buttressed by religion, and that’s a topic to discuss tomorrow.

Friday, May 15, 2009

Eternity and Ham, Part I

From time to time, we all think about eternity. But our thoughts differ. The great English poet Henry Vaughan (1621-1695) began his poem “The World”:

I saw eternity the other night

Like a great ring of pure and endless light,

All calm as it was bright . . .

I’ve always loved that poem. There is something so matter of fact about it. I imagine Henry Vaughan, who made his living practicing medicine, waking up to talk to his wife with those words. Just the same as you or I might mention an acquaintance we’d run into at the grocery.

The eternity I’ve been thinking about, unfortunately, is not Vaughan’s, but Dor othy Parker’s (1893-1967), who said “Eternity is two people and a ham.” If you don’t know Dorothy Parker, you should. She was a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table, perhaps the most celebrated gathering of American bon vivants ever. If you know anything she said it’s most likely:

othy Parker’s (1893-1967), who said “Eternity is two people and a ham.” If you don’t know Dorothy Parker, you should. She was a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table, perhaps the most celebrated gathering of American bon vivants ever. If you know anything she said it’s most likely:

Men seldom make passes

At girls who wear glasses.

I don’t think that’s nearly as clever as her description of Los Angeles as “Seventy-two suburbs in search of a city” (she was a confirmed New Yorker) or the words she requested for her tombstone “This is on me.”

But to return to my topic (sort of), for the last five weeks I’ve been struggling with a ham. A very nice ham, a Hormel Cure 81, which is the best regularly produced commercial ham in the United States. It was the leftover from our Easter Dinner and unfortunately, it wasn’t two people and a ham, it was me alone. My wife and daughter eat very little (which explains why they are thin and I am not) and have very busy social calendars. That means most every night since Easter it’s been me against the ham—mano y mano.

I lost. I ate ham sandwiches; ham omelets; ham and eggs; ham salad; salads with ham and almost every other variation of ham I could imagine. I made and ate a gallon of Senate Bean Soup, one of the most traditional, and boring, recipes in America (you can find the recipe here: http://www.cooks.com/rec/view/0,1748,144160-243193,00.html,

among other places).

The travel guide Frommer’s says, “The Senate Bean Soup may be famous, but it’s tasteless goo.” Frommer’s isn’t far off the mark. Anyway, after five weeks, the ham finally went bad, just when I was about to make ham croquettes. So I have faced eternity and lost.

(and please, don’t be scared, but there is a part two to this essay!)

I saw eternity the other night

Like a great ring of pure and endless light,

All calm as it was bright . . .

I’ve always loved that poem. There is something so matter of fact about it. I imagine Henry Vaughan, who made his living practicing medicine, waking up to talk to his wife with those words. Just the same as you or I might mention an acquaintance we’d run into at the grocery.

The eternity I’ve been thinking about, unfortunately, is not Vaughan’s, but Dor

othy Parker’s (1893-1967), who said “Eternity is two people and a ham.” If you don’t know Dorothy Parker, you should. She was a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table, perhaps the most celebrated gathering of American bon vivants ever. If you know anything she said it’s most likely:

othy Parker’s (1893-1967), who said “Eternity is two people and a ham.” If you don’t know Dorothy Parker, you should. She was a founding member of the Algonquin Round Table, perhaps the most celebrated gathering of American bon vivants ever. If you know anything she said it’s most likely:Men seldom make passes

At girls who wear glasses.

I don’t think that’s nearly as clever as her description of Los Angeles as “Seventy-two suburbs in search of a city” (she was a confirmed New Yorker) or the words she requested for her tombstone “This is on me.”

But to return to my topic (sort of), for the last five weeks I’ve been struggling with a ham. A very nice ham, a Hormel Cure 81, which is the best regularly produced commercial ham in the United States. It was the leftover from our Easter Dinner and unfortunately, it wasn’t two people and a ham, it was me alone. My wife and daughter eat very little (which explains why they are thin and I am not) and have very busy social calendars. That means most every night since Easter it’s been me against the ham—mano y mano.

I lost. I ate ham sandwiches; ham omelets; ham and eggs; ham salad; salads with ham and almost every other variation of ham I could imagine. I made and ate a gallon of Senate Bean Soup, one of the most traditional, and boring, recipes in America (you can find the recipe here: http://www.cooks.com/rec/view/0,1748,144160-243193,00.html,

among other places).

The travel guide Frommer’s says, “The Senate Bean Soup may be famous, but it’s tasteless goo.” Frommer’s isn’t far off the mark. Anyway, after five weeks, the ham finally went bad, just when I was about to make ham croquettes. So I have faced eternity and lost.

(and please, don’t be scared, but there is a part two to this essay!)

Thursday, May 14, 2009

Convention Center Hotel: Thoughts on the Results

If you had any interest in the results to begin with, then I’m sure you already know that the proposed Charter Amendment to prohibit the City of Dallas from owning a hotel (Proposition 1) failed last Saturday. I am pleased that the hotel will probably (barring some additional problems) now be built, but I’m a little concerned about the election results and what I have learned about the processes behind them.

The vote on Proposition 1 failed by 2,095 votes or .37% of the registered voters in the City of Dallas—that’s 37/100 of one percent, not 37%. The overall turnout rate for the City of Dallas County was about 15.8%. That means that 43,382 voted for the hotel; 41,287 voted against it; and 477,210 people didn’t vote. The total number of signatures required to get a vote on a charter amendment is 20,000 or slightly over 3.7% of registered voters—only about one third as many as would be required to change a city ordinance. That makes no sense. It would be as if it was easier to change the United States Constitution than a law enacted by Congress.

Granted a convention center hotel isn’t something that will affect most people’s lives, so I’m sure that depressed the turnout. But, on the other hand, about $8 million was spent on the election campaign (or about $100 for each vote actually cast), and one would think that might have increased the number of voters. I worry that some obscure ballot initiative proposed by special interests could be placed on the ballot and pass because not enough voters understood it and were willing to make the effort to vote.

I did a search and found a job listing on Craig’s List that paid $1.50 per signature for election petitions. A 75% validity rate was required. That means the cost to get an amendment to the Charter of the City of Dallas (that’s the “Constitution” for the city) is about $26,600. That’s way too cheap. You don’t want to eliminate the right to ballot initiatives, but a substantial issue should have more support and volunteers willing to gather signatures.

Proposition 2, which also was defeated on Saturday, is the best example of why the current rules are a problem. It was put on the ballot for spite. A New York union put it on the ballot because it was upset that it wasn’t guaranteed jobs in the proposed Convention Center Hotel project. Proposition lost 58% to 42%, but if it had passed, it would have required a popular vote on any subsidy for a private project in excess of $1 million. Waiting for a vote for each subsidy would have substantially slowed down any future development in the City, and Proposition 2 got 42% of the vote, even with no real campaign in favor of it.

It isn’t hard to imagine a proposition getting passed more or less by accident that is bad for the city and good for some special interest.

What ought to be done? Several states (Missouri, North Dakota, Oregon, Ohio, and Montana) have outlawed paying by the signature during petition drives. The federal courts have taken different positions on whether that restriction is legal, and in any event it would take action by the State of Texas.

Perhaps the best solution would be to amend the Dallas City Charter to require the same number of signatures (10% of registered voters) to put a charter amendment on the ballot as it does for an ordinance. That would increase the number of signatures to about 56,000 and almost triple the cost to put an amendment on the ballot by paying for signatures.

For only about $26,600—the cost of 20,000 signature, you could put this idea on the ballot for the next city election!

The vote on Proposition 1 failed by 2,095 votes or .37% of the registered voters in the City of Dallas—that’s 37/100 of one percent, not 37%. The overall turnout rate for the City of Dallas County was about 15.8%. That means that 43,382 voted for the hotel; 41,287 voted against it; and 477,210 people didn’t vote. The total number of signatures required to get a vote on a charter amendment is 20,000 or slightly over 3.7% of registered voters—only about one third as many as would be required to change a city ordinance. That makes no sense. It would be as if it was easier to change the United States Constitution than a law enacted by Congress.

Granted a convention center hotel isn’t something that will affect most people’s lives, so I’m sure that depressed the turnout. But, on the other hand, about $8 million was spent on the election campaign (or about $100 for each vote actually cast), and one would think that might have increased the number of voters. I worry that some obscure ballot initiative proposed by special interests could be placed on the ballot and pass because not enough voters understood it and were willing to make the effort to vote.

I did a search and found a job listing on Craig’s List that paid $1.50 per signature for election petitions. A 75% validity rate was required. That means the cost to get an amendment to the Charter of the City of Dallas (that’s the “Constitution” for the city) is about $26,600. That’s way too cheap. You don’t want to eliminate the right to ballot initiatives, but a substantial issue should have more support and volunteers willing to gather signatures.

Proposition 2, which also was defeated on Saturday, is the best example of why the current rules are a problem. It was put on the ballot for spite. A New York union put it on the ballot because it was upset that it wasn’t guaranteed jobs in the proposed Convention Center Hotel project. Proposition lost 58% to 42%, but if it had passed, it would have required a popular vote on any subsidy for a private project in excess of $1 million. Waiting for a vote for each subsidy would have substantially slowed down any future development in the City, and Proposition 2 got 42% of the vote, even with no real campaign in favor of it.

It isn’t hard to imagine a proposition getting passed more or less by accident that is bad for the city and good for some special interest.

What ought to be done? Several states (Missouri, North Dakota, Oregon, Ohio, and Montana) have outlawed paying by the signature during petition drives. The federal courts have taken different positions on whether that restriction is legal, and in any event it would take action by the State of Texas.

Perhaps the best solution would be to amend the Dallas City Charter to require the same number of signatures (10% of registered voters) to put a charter amendment on the ballot as it does for an ordinance. That would increase the number of signatures to about 56,000 and almost triple the cost to put an amendment on the ballot by paying for signatures.

For only about $26,600—the cost of 20,000 signature, you could put this idea on the ballot for the next city election!

Wednesday, May 13, 2009

Pobrecito!

This poor little fellow is, as far as I know, the only one of his kind in the State of Texas. It’s a pimiento de padron, a type of pepper grown in Spain and usually served as a tapa. The peppers are about the size and color of a small jalapeno, but thinner walled.

Preparing them is simplicity itself. You fry them in olive oil until they wilt, sprinkle them with salt and then serve. The taste is fresh and bright. Pimientos de padron are easy to make, cheap, delicious, and relatively healthy. The second picture shows them as they are served in tapas bars in Spain. They are just about the perfect snack food.

After a trip to Spain with my wife, I decided I had to try to grow them—because I don’t know of anyplace in the United States outside of New York or San Francisco where you can buy pimientos de padron. I searched the internet until I found somebody selling seeds for pimientos de padron and carefully started them in a hotbox that I had built to protect them against freezing.

Almost four months later I had only this one little pepper. Some of the seeds didn’t germinate. I lost some plants to too much or too little water. By the time I transplanted the pimientos de padron into larger pots I was down to three plants. Two of them immediately died. I still hope this one pepper will grow up and produce a bumper crop for me, because I grew to love eating pimientos de padron.

Such are the chances of life—and pimientos de padron are all about random chances and the vicissitudes of life. Because one of the main attractions of these little peppers, besides their great taste, if that while 90% of them are mild, the remaining 10% are as hot as jalapenos. Sometimes you can eat a whole plate and never find a hot one; sometimes you can get several hot peppers in a row.

You can be chatting pleasantly away and working your way through a glass of wine and a couple of plates of tapas when suddenly you bite into a hot one, turn red, and start sweating—or more amusingly, maybe that happens to one of your friends at the table. The concept of combining eating with a game of chance is enormous fun.

Preparing them is simplicity itself. You fry them in olive oil until they wilt, sprinkle them with salt and then serve. The taste is fresh and bright. Pimientos de padron are easy to make, cheap, delicious, and relatively healthy. The second picture shows them as they are served in tapas bars in Spain. They are just about the perfect snack food.

After a trip to Spain with my wife, I decided I had to try to grow them—because I don’t know of anyplace in the United States outside of New York or San Francisco where you can buy pimientos de padron. I searched the internet until I found somebody selling seeds for pimientos de padron and carefully started them in a hotbox that I had built to protect them against freezing.

Almost four months later I had only this one little pepper. Some of the seeds didn’t germinate. I lost some plants to too much or too little water. By the time I transplanted the pimientos de padron into larger pots I was down to three plants. Two of them immediately died. I still hope this one pepper will grow up and produce a bumper crop for me, because I grew to love eating pimientos de padron.

Such are the chances of life—and pimientos de padron are all about random chances and the vicissitudes of life. Because one of the main attractions of these little peppers, besides their great taste, if that while 90% of them are mild, the remaining 10% are as hot as jalapenos. Sometimes you can eat a whole plate and never find a hot one; sometimes you can get several hot peppers in a row.

You can be chatting pleasantly away and working your way through a glass of wine and a couple of plates of tapas when suddenly you bite into a hot one, turn red, and start sweating—or more amusingly, maybe that happens to one of your friends at the table. The concept of combining eating with a game of chance is enormous fun.

Tuesday, May 12, 2009

CityWalk@Akard Move-In Criteria

For those of you on our Call Back List for CityWalk and those considering adding their names to the list, here are some things you will need to know:

There is a Move-In Criteria. Simply put:

Identification – a valid driver’s license or other government issued photo I.D. and one of the following: Social Security card; Form I-94 Arrival-Departure Record; temporary resident alien card verifying approved entry by the U.S. government (I-94 W) or Permanent Resident card (I-551 – Alien Registration Receipt card), Temporary Resident Card (I-688) or Employee Authorization Card (I-688A).

Job Stability or Recurring Income – employment verification, subsidy or SSI verification or self-employment verification.

Credit Record – 24 months excluding student loans and medical accounts.

Rental History – where applicable.

Criminal Background – An applicant will automatically be denied in the event of 1) a felony conviction or received adjudication for felony offense(s) within the past ten years; or 2) any felony or misdemeanor conviction involving violence against persons. Applicants with a nonviolent felony conviction more than ten years in the past or a misdemeanor conviction may be considered on a case-by-case basis.

The interview process will be two fold: An interview will be scheduled with Central Dallas Community Development followed by an interview with Pinnacle Property Management personnel.

The interview process will begin in June and people will be contacted in the order their names appear on the call back list.

There is a Move-In Criteria. Simply put:

Identification – a valid driver’s license or other government issued photo I.D. and one of the following: Social Security card; Form I-94 Arrival-Departure Record; temporary resident alien card verifying approved entry by the U.S. government (I-94 W) or Permanent Resident card (I-551 – Alien Registration Receipt card), Temporary Resident Card (I-688) or Employee Authorization Card (I-688A).

Job Stability or Recurring Income – employment verification, subsidy or SSI verification or self-employment verification.

Credit Record – 24 months excluding student loans and medical accounts.

Rental History – where applicable.

Criminal Background – An applicant will automatically be denied in the event of 1) a felony conviction or received adjudication for felony offense(s) within the past ten years; or 2) any felony or misdemeanor conviction involving violence against persons. Applicants with a nonviolent felony conviction more than ten years in the past or a misdemeanor conviction may be considered on a case-by-case basis.